Oak Bluffs: from Sheep Pasture to Summer Colony

This week we’re taking a look at the evolution of Oak Bluffs from sheep pastureland and religious campground to summer colony and the political machinations of its struggle for independence from Edgartown.

Oak Bluffs as we know it today started with the first camp meeting organized by six men from the Edgartown Methodist Church, led by Jeremiah Pease. Pease and his affiliates had found a “venerable grove of oaks” in a sheep pasture in the northern part of Edgartown, today’s Oak Bluffs. The fate of the sheep is not recorded, but the first meeting, starting on August 24, 1835 was an immediate success, with sixty-five people converted and  six souls reclaimed. This pioneer congregation was made up of Islanders but good news spreads fast, and in 1836 there were visitors from a number of mainland towns as well. By 1842, 2,500 persons gathered for the “Big Sunday-sabbath” and in 1860 it was estimated that 12,000 people came to the grove for the closing ceremonies.

six souls reclaimed. This pioneer congregation was made up of Islanders but good news spreads fast, and in 1836 there were visitors from a number of mainland towns as well. By 1842, 2,500 persons gathered for the “Big Sunday-sabbath” and in 1860 it was estimated that 12,000 people came to the grove for the closing ceremonies.

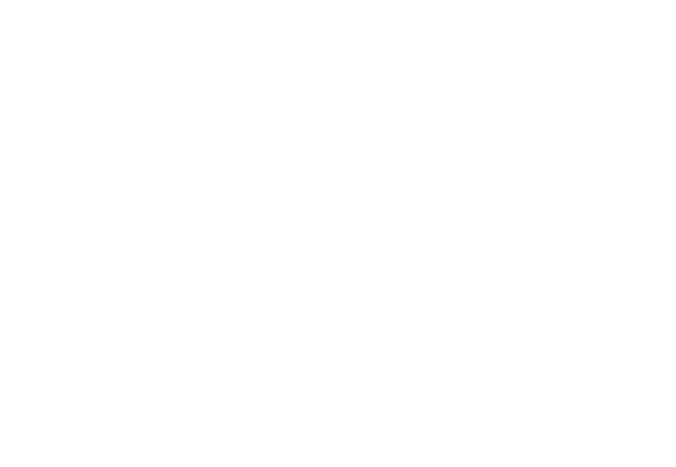

By the end of the Civil War, and thanks in part to the ride in the steamship and railroad, the East Chop campground had become the favorite camp meeting among New Englanders. The campground, now called Wesleyan Grove, consisted of tents for individual families with walls to separate men and women. Permanent structures started to appear by the middle of the 19th century and the first wooden gingerbread cottage was erected in 1859. The tabernacle as we know it today was built in 1879 to replace a the original tent (4000 square yards of sailcloth, drawn 54’ high at the center).

One of those post-Civil War visitors was Erastus P. Carpenter a wealthy industrialist from Foxboro, MA who arrived in 1865. With its crude tents, poor quality food, and smelly privies, Carpenter, the owner of the world’s second largest straw manufacturing plant, was accustom to the good life and found the conditions of the campground incompatible for his lifestyle. He was not a typical pilgrim, nor one happy to give up his comfort to find his God, but he had no choice if he wanted to participate in the revivals each summer at the Wesleyan Grove.

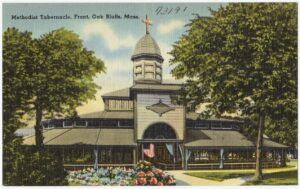

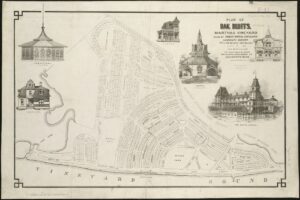

This is when he saw an opportunity: he would make the area around Wesleyan Grove available to all, a secular development. With his partners he created the Oak Bluffs Land & Wharf Company, whose incorporation included the first use of the name “Oak Bluffs”, although the community would be known as Cottage City until 1907. Erastus Carpenter’s company purchased the land around Wesleyan Grove sufficient to create 1000 house lots.

Until 1866 campground visitors to today’s Oak Bluffs all arrived from a dock in Eastville, on the other side of East Chop, and then by horse and buggy to the main entrance to the campground in front of today’s Summer Camp Hotel (the old Wesley House). In 1866 the Oak Bluffs Land & Wharf Company built a new on the Vineyard Sound side of East Chop which is still in use today as the primary arrival terminal for the Steamship Authority. 150 years later we are all the beneficiaries of Erastus Carpenter’s decision to move Cottage City’s front door to the ocean side of town with the construction of the wharf we still use.

Watching all this activity, the camp-meeting folks became worried about the denizen of secularists coming to the Vineyard and quickly built a seven-foot-high picket fence around the 35 acres of campground to keep out the heathens. In addition they purchased land on the other side of Lake Anthony (today’s East Chop Beach Club) and built a new wharf so that the religious devotees could arrive without being contaminated by the secularists arriving at Erastus Carpenter’s wharf. It took about seven years, but eventually the campgrounders realized that the secularists were actually not such bad people and the barriers were removed.

Carpenter wanted his development to be a “jewel” of which he would be proud. He hired Boston landscaper architect Robert Morris Copeland, famous for designing many of New England’s great cemeteries of that time, to create the first planned residential community in the United States. Cottage City was designed even before the oft credited first planned community, Riverside, Illinois, was designed by Frederic Law Olmsted in 1869. Carpenter insisted on breathing space and created Ocean Park, Waban Park and many others. He wanted Ocean Park, at the head of the new wharf, to provide a dramatic first impression of the Vineyard. The drama of the park, still apparent today, helped to facilitate the sale of 1000 lots.

Sales were brisk. In the first three years more than 500 lots were sold. In the following two years, 300 more. Never since, even up to the present time, has the Vineyard experienced such a torrid period of sales and real estate activity. Carpenter sold lots to many of the wealthy men, the nouveau riche, who had made their fortune in the post-Civil war industrial boom. These buyers weren’t welcome in old moneyed places like Newport, RI and they came to the new Cottage City in droves.

Sales were brisk. In the first three years more than 500 lots were sold. In the following two years, 300 more. Never since, even up to the present time, has the Vineyard experienced such a torrid period of sales and real estate activity. Carpenter sold lots to many of the wealthy men, the nouveau riche, who had made their fortune in the post-Civil war industrial boom. These buyers weren’t welcome in old moneyed places like Newport, RI and they came to the new Cottage City in droves.

In 1872 Carpenter’s company built the massive Sea View Hotel at the head of the wharf. Years later, Henry Beetle Hough Owner of the Vineyard Gazette wrote:

“It was a legend…One saw it from the steamboat, dominating the waterfront; one sat on the broad verandas which completely encircled it; the accommodations were the finest…it was a colossus, a marvel not only in itself, but because it transformed the whole aspect, the whole character of the community. Its towers were an imaginative flight, its whole effect was that of a fantasy, a wish-fulfillment, of the time. Like some chateau of dreams it stood, magnificent.”

The Sea View Hotel was a 19th century Disneyland. Its magnificence exuded confidence, a feeling of success. So much so, that other eager land developers moved in; dividing the remaining pasture land into 1000’s of additional lots. Cottage City was on the map. So much so that President Grant made a point to visit in the summer of 1874.

Meanwhile, back in the early 1870’s old Edgartown, looking on with envious and eager eyes. The old town was a depressed community since the end of whaling days. Edgartown desperately needed new economic opportunities. Watching all the dramatic growth of Cottage City, Edgartown voted to invest $40,000 in a new road connecting the two areas (today’s beach road) and then an additional $15,000 to build a railroad connecting the two areas and Katama, where Erastus Carpenter was planning his second act: a hotel and residential development along South Beach called Mattakesett. Most of the funds for the road and railroad were assessed to the residents of Cottage City, taxpayers of Edgartown, who were, in fact subsidizing the project that was to siphon business away from Cottage City!

Katama was not a success at that time due to its remote location and Edgartown didn’t benefit as its residents had hoped. Success in these areas would come, but not until after the invention of the automobile many decades later. But there was no denying that Erastus Carpenter and his Oak Bluffs Land & Wharf Company had created a success and placed the Vineyard on the map. So much so that Cottage City property owners by the mid 1870’s now provided more than half of Edgartown’s tax revenues but received very limited services. Residents began demanding more services, most of all, better fire protection.

Katama was not a success at that time due to its remote location and Edgartown didn’t benefit as its residents had hoped. Success in these areas would come, but not until after the invention of the automobile many decades later. But there was no denying that Erastus Carpenter and his Oak Bluffs Land & Wharf Company had created a success and placed the Vineyard on the map. So much so that Cottage City property owners by the mid 1870’s now provided more than half of Edgartown’s tax revenues but received very limited services. Residents began demanding more services, most of all, better fire protection.

Edgartown’s leaders were weary of the demands. From their perspective Cottage City summer residents were getting too big for their britches. It was just a summer colony and yet, it was getting all the press attention. To off-islanders Cottage City had become “Martha’s Vineyard”.

Control of town meetings was securely in the hands of old Edgartown, guaranteeing that most of the tax money was spent there. This created friction with the mostly seasonal residents of Cottage City. They had been taxed to build both the road and railroad to Edgartown with the goal of draining business from Cottage City with no corresponding benefits to improve Cottage City.

And so begins the next remarkable part of this story: the secession of Cottage City from Edgartown in 1880. Momentum had been building in Cottage City to secede from Edgartown but old Edgartown controlled the vote so the legislative representative from the Vineyard to Boston wouldn’t allow a vote on the issue.

That changed in the summer of 1879 when, innocently or not, the first Board of Health Agent in Edgartown declared that the water at the Vineyard Grove House, a hotel in Cottage City that coincidentally was owned by a leader of the secession drive, was contaminated and that visitors to Cottage City needed to know that the water was unfit for human consumption. A ruckus ensued and Cottage City leaders were convinced this was retribution and that there had to be a major change. It must elect a state representative who would support its petition to secede. But how could this happen, old Edgartown had always controlled the county vote to elect the legislative representative?

Coincidentally, that year, the residents of Gay Head formed a Town (previously the residents of the Town, mostly Wampanoag Indians, had lived on a “plantation” and they were denied the vote until they incorporated into a Town) They wanted change and they voted en masse for the candidate proposed by Cottage City. By a slim margin (due to the help of the Gay Head vote) the Cottage City candidate won the vote and wrestled the control of the County from old Edgartown proper to Cottage City. That followed with a successful petition to the Massachusetts Legislature to secede, approved on February 17, 1880.

The Edgartown political machine didn’t take the results without protest, and demanded that the state investigate several improprieties it said had occurred in the voting. But the state confirmed the vote as legitimate and Cottage City became its own Town and in 1907 changed its name to Oak Bluffs, as we know it today.

Animosity between the two towns continued for another generation. It should also be mentioned that after winning the vote there was no mention in any of the news accounts of the importance of the Gay Head vote. Even on Martha’s Vineyard those were still the days of strict segregation.

Camp Meetings were primarily Methodist but in the mid-1870’s the Baptist Association started to have its own camp meetings in East Chop. These meetings attracted the interest of Charles Shearer, a profoundly religious man, whose father was a Virginian Plantation Owner and his mother was a slave. He was a staunch Baptist.

He and his wife loved the Vineyard and in the late 1880’s purchased their first property on the island – later to become a commercial laundry and then a seasonal inn, catering to African Americans who, at that time, were not welcome at other island establishments. The inn thrived. The building is located on Morgan Avenue, just across the street from where the Ocean View restaurant was located and is still under ownership of members of the Shearer family.

Although people of African descent first arrived on the Vineyard in the 1600’s it wasn’t until after slavery was abolished that freed blacks came to work on the island in the fishing industries and started businesses on the Vineyard, ultimately, transforming it into the country’s best-known and most exclusive African American vacation destination.

The Vineyard wouldn’t be what it is today without the ascendancy of Cottage City in the mid to late 19th century. The dynamic growth of Cottage City resulted in its secession from Edgartown. Unlike the other sleepier Vineyard towns of the time, Tisbury, West Tisbury, Chilmark and Aquinnah, the separation of today’s Oak Bluffs from Edgartown gave dynamism to the uniquely different cultures of the six island towns we celebrate today as part of the Vineyard’s unique heritage.